Click here to get this post in PDF

At 63, Arline Mann knew she was ready to leave her career as a lawyer and Managing Director

at Goldman Sachs. For nearly three years before her departure, she had quietly reflected on

what might come next. What she could not have anticipated was what actually awaited her.

Arline loved her job at Goldman from her first day to her last. She spent nearly 25 years there, most of them as head or co-head of the Global Employment Law Group, a position she created. The work was fast-paced, complex, and demanding. She thrived under pressure and found deep satisfaction in working with people she respected. But she knew when the time was right to step away.

One powerful influence was her parents’ experience with longevity. Her father lived to 95 and her mother nearly to 102. Watching them navigate extreme old age made Arline focus closely on her own future. She fully expected she might have another 30 years of life ahead of her, almost as long as her entire legal career. Her parents’ retirement was pleasant and comfortable. They spent time with friends and family, danced, traveled a bit, and volunteered. All lovely. But 30 years of that?

Arline belongs to a generation that expects not only to live longer, but to live that time well. It is a generation whose careers were often not just financially rewarding, but deeply engaging and fulfilling. For her, retirement could not simply mean classes, gardening, volunteering, or travel. And she had no interest in a diluted version of her former life as a lawyer. She wanted something with the same level of challenge and adventure she had found at Goldman, just in an entirely different form.

She had very little idea of where and how to direct that ambition and drive.

“There are some lucky retirees who know exactly what they want to do,” Arline says. “Often

they’ve had a strong secondary interest throughout their lives, something they’ve pursued

alongside their main careers. When they retire, they simply pick it up full force. I didn’t have that. Or at least, I thought I didn’t.”

So several years before leaving Goldman, Arline began talking to every recently retired person

she happened to meet. She also started a running list of possibilities for herself. “I put

everything on that list that sounded even remotely interesting or fun, no matter how nutty,” she

recalls. “Writing (not nutty), professional detective work (kind of nutty), fountain design

(nutty).”

But making a list, she learned, was only the beginning. “If you just sit with a list and try to decide what you’d like to do, you’ll do nothing,” she says. “You have to try things on to see how they feel emotionally and whether they really use your skills.”

There were false starts. At first, writing seemed like the most promising path. It connected to

a childhood interest and would put her drafting skills to use. She spent a year

researching a nonfiction book idea, and the research was great fun. But when it came time to

actually write, she realized she was not motivated to do it.

So it was back to the drawing board, literally.

Art had always been part of Arline’s life. For decades, she spent weekends in museums,galleries, and auction houses. She continued drawing and painting into her teen years but, like many people, assumed that without immediate talent, you couldn’t go very far.

Simply grabbing the next possibility from her list, Arline decided to enroll in a few basic drawing classes. In the first two courses, her instructors pulled her aside and encouraged her to continue, telling her she “had something.” And slowly, she came around to the idea that artistic skill, like any other skill, could be learned, especially by someone who had been observing and absorbing art her entire life.

She soon began regular watercolor classes at the Art Students League. It quickly became clear

that this was not a passing interest. This was what she wanted to pursue seriously, likely for the

rest of her life.

Although, Arline understood there were limits to what could be accomplished beginning late in life. She sought guidance from her main instructor on how to become the strongest artist possible within that reality, and continued to study and to learn. She found that her ambition and work ethic had not faded. She was as driven as she had been in law.

Within a year, she made a pivotal decision that this would not be a hobby. She began submitting

her work to competitive exhibitions, successfully.

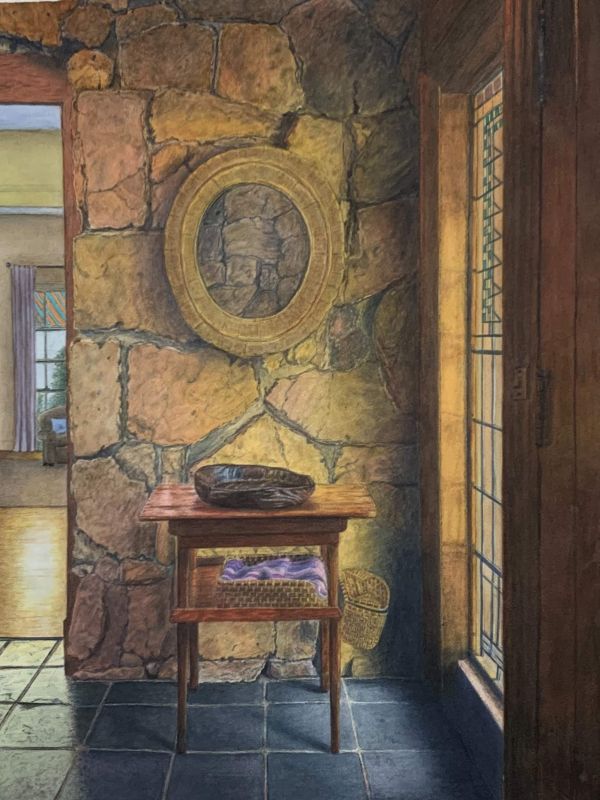

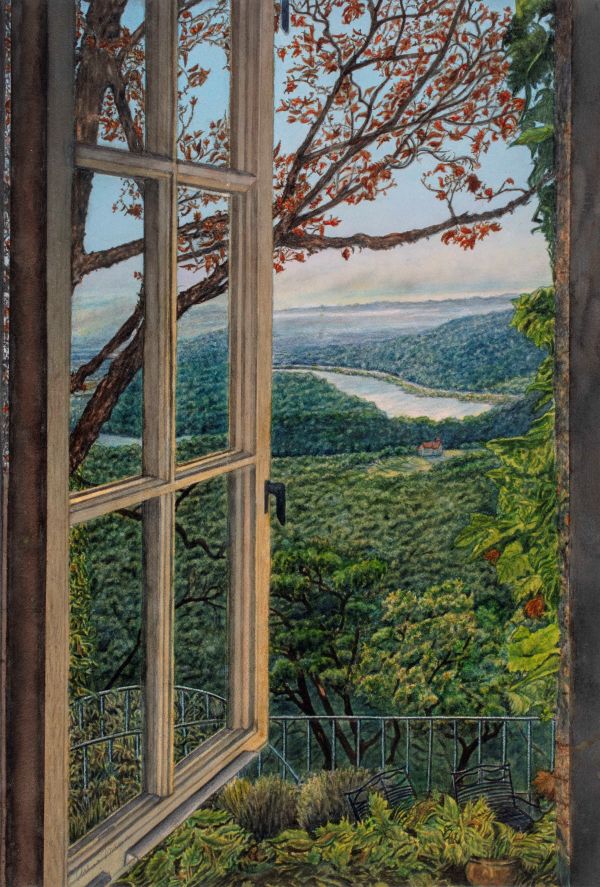

Today, Arline’s work has been included in more than 40 competitive national and international

exhibitions. She has had several solo shows, including a museum exhibition. Her work has been

featured in multiple art publications and has earned numerous awards.

This type of retirement reaches for the future. It is about creating work, building visibility, and

continuing to grow. It is challenging, fresh, and at times intimidating. It requires learning entirely

new technical skills while also drawing on the business insight she cultivated over decades.

“In interacting with galleries and museums, for example, you have to understand what the person or institution on the other side of the table needs,” she notes. “That is a basic business attitude as applicable in the art world as it is anywhere, including life in general.”

For Arline, this second act is not a quiet slowing down. It is an expansion. An intentional reinvention of retirement built with the same discipline, curiosity, and intensity that defined her career in law.

This is the retirement she hoped for: a full-throttle adventure down a new path.

You may also like: 7 Tips for Women Looking to Climb Up Further in Their Careers

Image source: Arline Mann